Alice Arlen has written much about Maine’s sporting camps. We are pleased to include the following article she wrote that nicely depicts what a “Traditional Maine Sporting Camp” is all about…

Introduction to In the Maine Woods:

An Insider’s Guide to Traditional Maine Sporting Camps

by Alice Arlen

In addition to my own thoughts, the following incorporates information from Gary Cobb’s The History of Pierce Pond Camps and Stephen Cole’s manuscript Maine Sporting Camps.

There is a grand tradition that has become an integral part of Maine’s heritage: Unique to the state, and over 140 years old, it is called the Maine sporting camp. Some people think of these camps as “hunting and fishing lodges.”

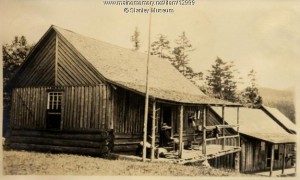

They are that, but they are also much more. Nearly all sporting camps are on a lake or river, generally in a remote area of forested land. Most have buildings made of peeled and chinked logs with porches looking over the water. The guest sleeping cabins are clustered near the shore around a central dining lodge. Plumbing was (and often still is) “out back.” Primitive, and in harmony with their surroundings, sporting camps have the appearance of having grown out of the ground.

New Hampshire and Vermont have private hunting and fishing clubs and game preserves. New York, in the Adirondacks, has private camps and rustic estates. But Maine sporting camps are open to paying customers and are a cultural and entrepreneurial resource distinctive to the state.

Several factors came together to produce the Maine sporting camps. The post-Civil War transition into the Victorian era saw tremendous industrial and economic expansion and the development of technologies such as the internal-combustion engine and electricity. The iron and steel industries flourished, and the railroads entered their golden age. The high economic growth rate in the Victorian era created a substantial upper-middle class.

At the same time, intellectuals and writers such as Henry David Thoreau decried what they saw as society’s growing alienation from nature and expressed general uneasiness about the direction of American culture. Life in polluted eastern cities during the Industrial Revolution was felt to be “undermining character, taste, morality, and the health and welfare of individuals and family.”

As a result, those who could sought escape from the questionable influences and pollution of the cities, as well as from the summer heat. (Ironically, many who “took the airs” were the families of magnates and managers whose factories were causing the pollution they were escaping.)

Recreational sailing and canoeing are lasting legacies of the Victorian era. Hunting, fishing, and hiking took on a certain cachet as sporting pursuits instead of merely functional activities. Not only did people have motives for escape (aesthetics, expendable income, leisure time, status, health concerns), they also had the means.

It is no coincidence that the heyday of fishing and hunting in Maine was also the golden age of lumbering and railroading. The very rail lines that were bringing trainloads of Maine timber to fuel factory burners also carried trainloads of vacationers fleeing back to the source of all that smog! With the growth of a national rail transportation network, an extended family vacation at one of the much-publicized public sporting camps in the Maine wilderness became possible and desirable.

The Bangor, the Aroostook, and the Central Maine Railroads all offered direct service to Brownville in 1881, to Presque Isle in 1882, to Katahdin Iron Works in 1883, and reached Moosehead Lake in 1884. The Somerset Railroad came to Bingham in 1890; the narrow- gauge trains got to Rangeley and Carrabassett by 1895; and the Katahdin, Allagash, and Fish River areas were opened by 1900.

Before Henry Ford put his first automobile on the road, place – names such as Sysladobsis, Oquossoc, Nesowadnehunk, and Munsungan were part of the vocabulary of hunters, angles, and vacationers from Boston to Philadelphia.

In 1904 there were at least 300 sporting camps in operation in Maine. In 1997, there were few more than the 78 herein recorded. After World War II, Americans could no longer spend the time or money on a month-long vacation at a Maine sporting camp. The railroads were in decline and automobiles and “motor coaches” were on the increase. The road system in Maine was poor and people stayed close to the tarmac, where motels and motor-coach campgrounds were now the rage.

And finally, air transportation took travelers out of New England altogether. Over the years, many camps burned, some became resorts, some sold as condominiums or individual cottages, and others simply rotted away to become part of the forest.

But good things die hard. In spite of these changes and setbacks, tucked away here and there stand sporting camps whose owners proudly struggle to maintain a tradition that may very well be the only stabilizing factor in the Maine woods.

Fortunately, these few hardy souls have held on long enough to witness a renewed interest in Maine sporting camps. We have come full circle. We need what sporting camps have to offer, now more than ever. There are precious few places where we can feel the fundamental connections with nature and with one another.

Sporting camps still provide solace for urban refugees (meaning most of us), and a wilderness playground for those who love the outdoors. Most of all, they still provide a much-needed “port in the storm,” far from the fractured, mobile, frenetic, and alienating forces that impose on our humanity.